Building a database: Part 1

In almost every project I ever built, a database was a central component. Often I’d read online about what specific database engines excelled in, and what they lacked. However, I never fully understood what this meant exactly. That always irritated me. I think in cases like this, the best way to learn more about a topic is to try to build something myself. So I set out with very little knowledge but a lot of optimism to try to build my own database engine.

This post is the first part of building a simple database engine from scratch. It covers:

- Requirements for a simple database

- How to store data on disk

- Key components of a database engine (WAL, Memtable, SSTables)

- First steps in implementation (in Go)

In follow up posts I will try and optimize the database and also expand upon its functionality.

Requirements

Before starting with anything, it is important to determine the database requirements. Clear requirements can direct the design while also preventing unnecessary work.

- Data written must be persistent (not lost on system restarts).

- The database must be crash resistant (Data must never be lost if the database reports that it’s inserted, even if the system crashes during a write).

- There should be a basic schema mechanism to define the structure of the data.

- It must support: strings, integers and booleans.

- It must support: Defining a primary key.

- There should be a way of interfacing with the database (inserting, reading, updating and deleting data).

- There should be a primary index to speed up finding data.

- The database should be optimized for quick writes.

Out of scope:

- Relations between data (so no joins)

- No secondary indexes (Indexes on fields other than the primary key)

- Ability to update existing table structures

Writing data to disk

A core part of a database is being able to store data persistently (on disk) and being able to search it.

There are many ways of achieving this. Modern databases often use one of two data structures to store data: B-Trees or SSTables. While B-Trees are very good at searching through the data quickly, it is inefficient to update a B-Tree stored on disk. SSTables excel at writing quickly, but are less optimized for reading. However, read speeds can be improved by optimization techniques like bloom filters and indexes. SSTables are used to power popular databases like CassandraDB. B-Tree’s are often used in relational databases where reading is very important, like PostgreSQL and MySQL. For this project we will use SSTables.

SSTables in practice

SSTables work by building a sorted string table on disk. When data is written to the database, it is initially stored in an in memory data structure. When the in memory data structure reaches a certain size, it is written to disk as an SSTable. The SSTable is immutable, and cannot be updated. This means mutations on existing records must be written to a new SSTable. Altered records become new entries with the same key in the memtable, which are later flushed to new SSTables, deleted records also become new entries and are tombstoned (marked as deleted).

Imagine a key value table written and stored on disk.

Table 1:

Key, Deleted, Value

1, False, "a"

2, False, "b"

3, False, "c"

6, False, "d"

At this point the user adds the record (4, ‘a2’), removed the record with id 2 and update the record 6 to value ‘d2’. These changes are written to a new table on disk:

Table 2:

Key, Deleted, Value

2, True, "b"

4, False, "a2"

6, False, "d2"

When the database is queried, we first look into table 2, and then table 1. This ensures the database always returns the most up to date information. A downside of this approach is that if a key is queried that is not in the database, all tables will have to be searched.

Compaction

With the SSTables method of storing data, a lot of potential duplication is introduced. In order to mitigate this, tables are compacted in the background over time. For example, the two tables above could be compacted into the following single table:

Table 3:

Key, Deleted, Value

1, False, "a"

3, False, "c"

4, False, "a2"

6, False, "d2"

By using a merge sort, it is efficient to merge 2 sorted lists into 1 sorted list.

SSTables enable quick writes, as the database only ever has to append to a file, which is much quicker than writing to a file in a random location.

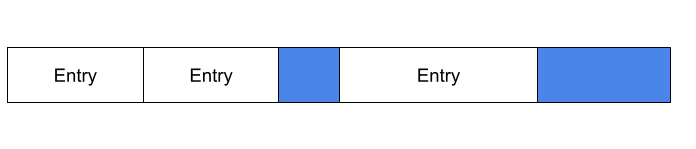

Blocks

It’s impossible to predict the length of an entry, it depends on what the user is storing. This means that if multiple entries are written to a SSTable, we cannot know where entries start and end without scanning the file from the beginning. To address this, SSTables are typically structured into blocks of fixed size. This opens the door for many possible search optimizations. Let’s investigate how these blocks are structured.

First we determine a static size for each block, typically around 2KB. We adhere to the following rules when writing to block:

- Each block always starts with a new entry to ensure entries are never split across block boundaries.

- If an entry cannot be added to a block without exceeding the remaining space in the block, the entry is added to a new block. The current block is padded with empty bytes. Padding is important because we want blocks of fixed size, but also wastes some space on disk.

- To keep things simple if an entry is larger than the block size, it will never fit. The database will throw an error.

The image below shows a possible block layout on disk with a 10 byte block size. The first 2 entries are placed in the first block, which leaves 2 bytes left. The next entry is 6 bytes and does not fit. The current block is padded with 2 bytes (marked in blue), and the new entry is added to the next block.

In a later part, we can use the predictable block structure to build an index that contains information about what keys are in which block. This will will greatly increase search speed.

Database design

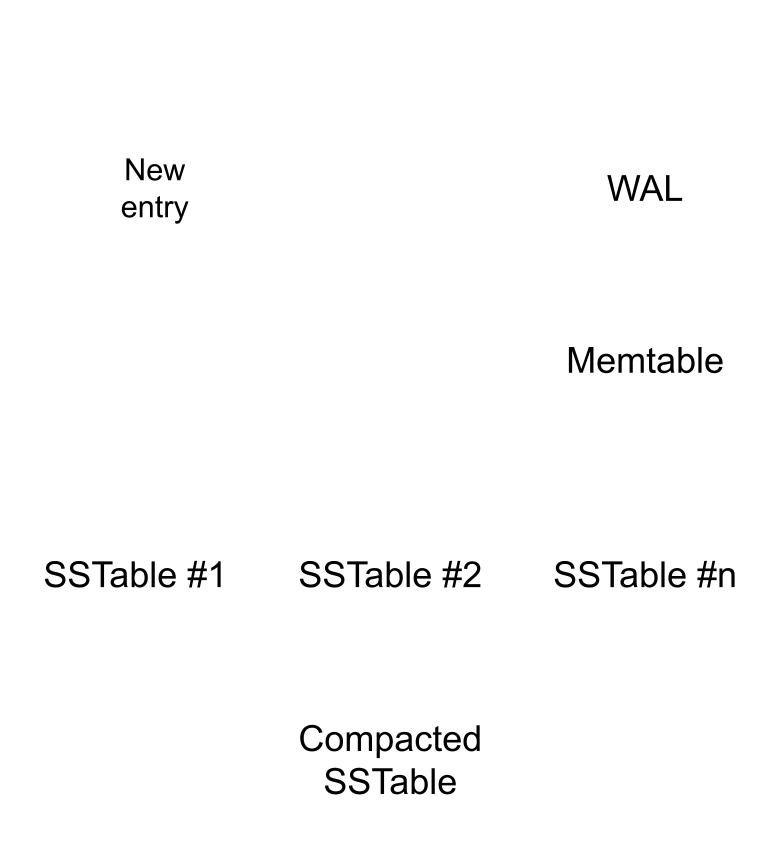

Alright, the SSTable provides a structure for storing data on disk optimized for insertion. However to have a working database, we need a few more components. In this section we cover the high level database design:

-

A memory table that stores recent operations on the database

-

A WAL (Write Ahead Log) to guarantee persistence of the memory table in case the computer shuts down

-

SSTables that store ordered rows.

When a user inserts a new record, the action is written to the WAL and inserted into the memory table (memtable). The memory table is ordered by the primary key, but the WAL is ordered by time. If the process crashes, all data in the memtable is lost. After restarting, the database process can replay the WAL to restore the memtable.

As more data is inserted over time, the memtable grows. When it has reached a certain size (e.g: 2MB). The table is written to a SSTable on disk. Over time the SSTables are compacted in the background.

Structuring files and tables

Each table in the database is given a separate directory with SSTables. The database also maintains a separate memtable per table. The WAL however is unified and contains the operations on all tables.

Of course the database needs to keep track of what tables exist. When the database is initialized, it will create a ‘book keeping’ table to store this information.

Database operations

Inserting data

If a user inserts a record, we write the insertion to the WAL and insert the row in the memtable in its appropriate ordered location.

Updating data

If a user updates a record, we update the data in the memtable, but if the record is not in there (because it’s been flushed to disk) it is simply added to the memtable as if it is an insertion.

Reading data

When a user queries a specific primary key, the database engine searches the memtable. If it isn’t there it then starts to search the most recent SSTable and all following SSTables until it finds it. This means that if the key is not in the database the process has to search everything. This part can be sped up by an indexing strategy.

Deleting data

Like updating we update the record by setting a deleted flag to true

A first implementation

Let’s start implementing some of the basic building blocks of the database. I have decided to use Golang as I’m familiar with it and it’s easy to read.

Memory table

First we implement the memtable component. We need the memtable to be able to support different types of table structures later on, so let’s design it with that in mind.

We’ll maintain an ordered list of entries. Each entry has a primary key, a deleted flag and a list of values. Depending on the table structure, the primary key might be a a string, int or bool. The values can also be any type. In order to support this the primary key and values with be stored as byte arrays. When reading the data, the database can lookup the table structure to determine how to interpret the byte values.

type Memtable struct {

entries *list.List

}

type MemtableEntry struct {

id []byte

values [][]byte

deleted bool

}

The memtable has functions for insert / update / get

func (m *Memtable) Get(id []byte) *MemtableEntry {

for e := m.entries.Front(); e != nil; e = e.Next() {

if bytes.Equal(id, e.Value.(MemtableEntry).id) {

entry := e.Value.(MemtableEntry)

return &entry

}

}

return nil

}

func (m *Memtable) Update(id []byte, values [][]byte) {

entry := MemtableEntry{

id: id,

values: values,

deleted: false,

}

for e := m.entries.Front(); e != nil; e = e.Next() {

if bytes.Equal(e.Value.(MemtableEntry).id, id) {

e.Value = entry

return

}

}

return

}

func (m *Memtable) Insert(id []byte, values [][]byte) {

entry := MemtableEntry{

id: id,

values: values,

deleted: false,

}

for e := m.entries.Front(); e != nil; e = e.Next() {

next := e.Next()

if next != nil && bytes.Compare(id, next.Value.(MemtableEntry).id) == -1 {

m.entries.InsertBefore(entry, next)

return

}

}

m.entries.PushBack(entry)

}

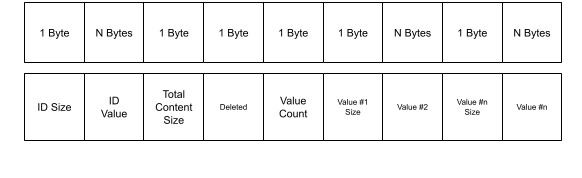

Serializing the data

In order to store the data on disk and in the WAL the data needs to be serialized. We’ll convert an entry into a byte array with the following format:

func (entry *MemtableEntry) Serialize() (int, []byte) {

var header bytes.Buffer

var content bytes.Buffer

header.WriteByte(byte(len(entry.id)))

header.Write(entry.id)

if entry.deleted {

content.WriteByte(1)

} else {

content.WriteByte(0)

}

content.WriteByte(byte(len(entry.values)))

for _, v := range entry.values {

content.WriteByte(byte(len(v)))

content.Write(v)

}

contentBytes := content.Bytes()

header.WriteByte(byte(len(contentBytes)))

bytes := append(header.Bytes(), content.Bytes()...)

return len(bytes), bytes

}

To read it back into the data structure:

func (entry *MemtableEntry) Deserialize(entryBytes []byte) error {

buf := bytes.NewBuffer(entryBytes)

idLen, err := mustReadByte(buf)

if err != nil {

return err

}

id, err := mustReadN(buf, int(idLen))

if err != nil {

return err

}

entry.id = id

_, err = mustReadByte(buf) //Discard content length

if err != nil {

return err

}

deleted_i, err := mustReadByte(buf)

if err != nil {

return err

}

entry.deleted = false

if int(deleted_i) == 1 {

entry.deleted = true

}

valuesCount, err := mustReadByte(buf)

if err != nil {

return err

}

for range valuesCount {

valueLen, err := mustReadByte(buf)

if err != nil {

return err

}

value, err := mustReadN(buf, int(valueLen))

if err != nil {

return err

}

entry.values = append(entry.values, value)

}

return nil

}

To test whether the serialization is working, we write some unit tests.

func TestSerializeDeserializeStr(t *testing.T) {

e := MemtableEntry{

id: []byte("abc"),

values: [][]byte{[]byte("a"), []byte("b")},

deleted: false,

}

_, s := e.Serialize()

e1 := MemtableEntry{}

e1.Deserialize(s)

if !reflect.DeepEqual(e, e1) {

t.Errorf("Deserialized struct does not match original.\n Expected \n%v \n got \n%v", e, e1)

}

}

func TestSerializeDeserialize(t *testing.T) {

e := MemtableEntry{

id: []byte{byte(9)},

values: [][]byte{[]byte("a"), []byte("b")},

deleted: false,

}

_, s := e.Serialize()

e1 := MemtableEntry{}

e1.Deserialize(s)

if !reflect.DeepEqual(e, e1) {

t.Errorf("Deserialized struct does not match original.\n Expected \n%v \n got \n%v", e, e1)

}

}

Creating the SSTable

When the memtable is full, we want to store it to disk. This is where the SSTable comes in. To build the table, we serialize each entry in the list. We then need to write to the block structure as defined before.

func CreateSSTableFromMetable(memtable *Memtable, blockSize int) (*SSTable, error) {

currentBlock := []byte{}

blocks := []byte{}

for e := memtable.entries.Front(); e != nil; e = e.Next() {

entry := e.Value.(MemtableEntry)

size, serialized_entry := entry.Serialize()

//Check to see if there is enough place in the block to add the entry

if size > (blockSize - len(currentBlock)) {

if size > blockSize {

//Will never fit

return &SSTable{}, errors.New("Entry larger than max block size")

}

//Pad remainder of block

padding := blockSize - len(currentBlock)

currentBlock = append(currentBlock, make([]byte, padding)...)

//Prepare new block

blocks = append(blocks, currentBlock...)

currentBlock = []byte{}

}

currentBlock = append(currentBlock, serialized_entry...)

}

padding := blockSize - len(currentBlock)

currentBlock = append(currentBlock, make([]byte, padding)...)

blocks = append(blocks, currentBlock...)

return &SSTable{Blocks: &blocks}, nil

}

func (table *SSTable) Flush(path string) error {

return os.WriteFile(path, *table.Blocks, 0644)

}

Searching in the SSTable

We can now do a very simple lookup in the table. This implementation is just to try it out, later we’ll replace this with a faster solution.

To prevent having to load the entire file in from memory we use the bufio package.

func SearchInSSTable(path string, searchId []byte) (MemtableEntry, error) {

for {

idSize := make([]byte, 1)

_, err := reader.Read(idSize)

if err != nil {

return MemtableEntry{}, err

}

if idSize[0] == byte(0) {

continue

}

id := make([]byte, int(idSize[0]))

contentLength := make([]byte, 1)

_, err = reader.Read(id)

if err != nil {

return MemtableEntry{}, err

}

_, err = reader.Read(contentLength)

if err != nil {

return MemtableEntry{}, err

}

if !bytes.Equal(id, searchId) {

reader.Discard(int(contentLength[0]))

continue

}

content := make([]byte, contentLength[0])

_, err = reader.Read(content)

if err != nil {

return MemtableEntry{}, err

}

all := []byte{}

all = append(all, idSize...)

all = append(all, id...)

all = append(all, contentLength...)

all = append(all, content...)

fmt.Printf("%v \n", all)

fmt.Println("")

entry := MemtableEntry{}

entry.Deserialize(all)

return entry, nil

}

}

To wrap up I’ll also write a unit test to see if the SSTable is working as expected.

func TestSSTable(t *testing.T) {

memtable = NewMemtable()

for id := range 10 {

memtable.Insert([]byte{byte(id)}, [][]byte{{byte(id)}, []byte("b")})

}

table, _ := CreateSSTableFromMetable(&memtable, 10)

tableBytes := table.Bytes()

fmt.Printf("%v", tableBytes)

reader := bufio.NewReader(bytes.NewReader(tableBytes))

for id := range 10 {

result, _ := SearchInSSTable(reader, []byte{byte(id)})

entry := MemtableEntry{

[]byte{byte(id)},

[][]byte{{byte(id)}, []byte("b")},

false,

}

if !reflect.DeepEqual(entry, result) {

t.Errorf("Result does not match query. \nExpected: \n%v\n Got:\n %v", entry, result)

}

}

}

Conclusion

In this post we went over some fundamental concepts for database design and implemented the basic building blocks. In the next post we’ll expand the database by implementing the WAL and adding the logic for maintaining and working with table structures.